By Aleksandar Levai @ Shutterstock.com

It has been my experience that publicly managed funds, such as pensions, tend to be backward looking. They embody a rear-view mirror way of investing that is, often times, easier to defend to a committee to save one’s job, but not necessarily the best investment strategy, as I explain here and here.

In another example of group-think, pensions are trying to “protect” against losses with a “crisis risk offset.” Sounds pretty serious. In reality, it’s a 20-year Treasury bond ETF that is almost guaranteed to lose money in an all but guaranteed rising interest rate environment.

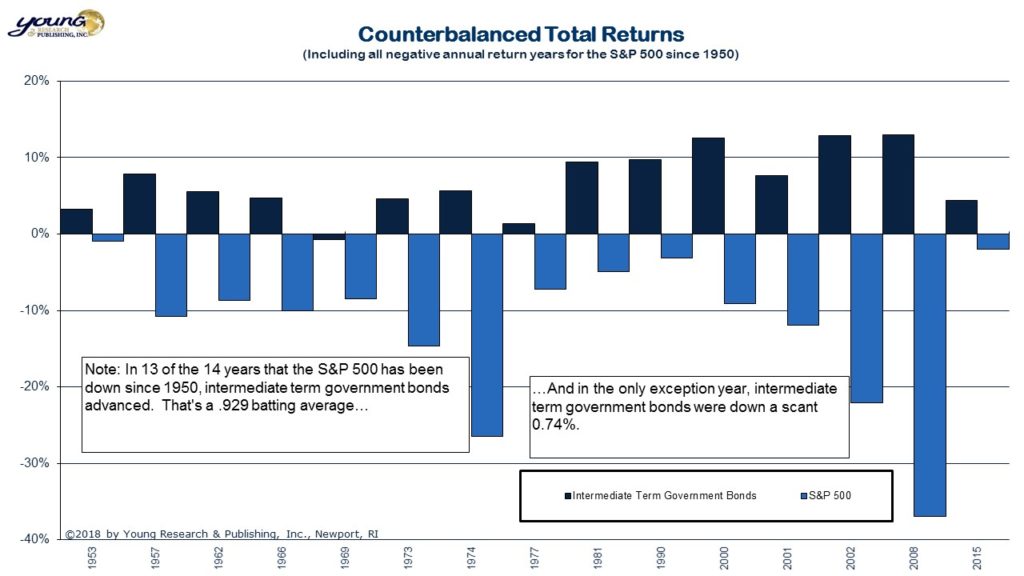

Remember, when it comes to bonds, the longer the maturity the larger the losses when rates increase. A much smarter Treasury strategy would be to keep the maturities short-term, with direct ownership using a bond ladder. It’s a much better crisis risk offset for today.

Gregory Zuckerman reports on the pension funds purchasing uncertain protection in The Wall Street Journal, writing:

Worried their portfolios were too risky, public-pension managers in California, Hawaii and Rhode Island have shifted more than $25 billion over two years or so into “crisis-risk offset” strategies, while others are in the process of such moves. Typically, these tactics aim to limit investor losses by buying long-term Treasury bonds, whose price often increases during market downturns, and investing in “trend following” hedge funds.

The crisis category was developed in just the past few years by consultants to address pension funds’ concerns that prices across many markets could fall in lockstep in the next recession, much as they did a decade ago, placing them at risk. But the limits of these strategies are coming into view with the sharp retreat that has rocked U.S. stock indexes in October.

For one thing, crisis-risk offset strategies are unlikely to provide much shelter if the value of long-term bonds comes under pressure, consultants say. Yet that is exactly what has been going on lately, as investors worry the economy’s strength and continued interest-rate increases by the Federal Reserve will pressure bonds.

The yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury note this month has hit its highest level since 2011, including an unusual rise during the early hours of Wednesday’s stock meltdown. Yields rise when bond prices fall. Though yields dropped in the latter stages of the past week’s tumult, many investors expect them to resume rising in coming months.

At the same time, trend-following tactics generally only work in an extended downturn of several weeks or even longer. That is because it takes a while for the funds’ models to adjust to lower stock prices.

Read more here.