In an October speech after the Fed decided to start expanding its balance sheet once again under the auspices of fixing problems in the repo market, Fed Chair Powell said,

I want to emphasize that growth of our balance sheet for reserve management purposes should in no way be confused with the large-scale asset purchase programs that we deployed after the financial crisis. Neither the recent technical issues nor the purchases of Treasury bills we are contemplating to resolve them should materially affect the stance of monetary policy, to which I now turn.

During the Q&A session following the prepared remarks Powell affirmed, “In no sense is this [Fed’s restarted bond buying program] QE.”

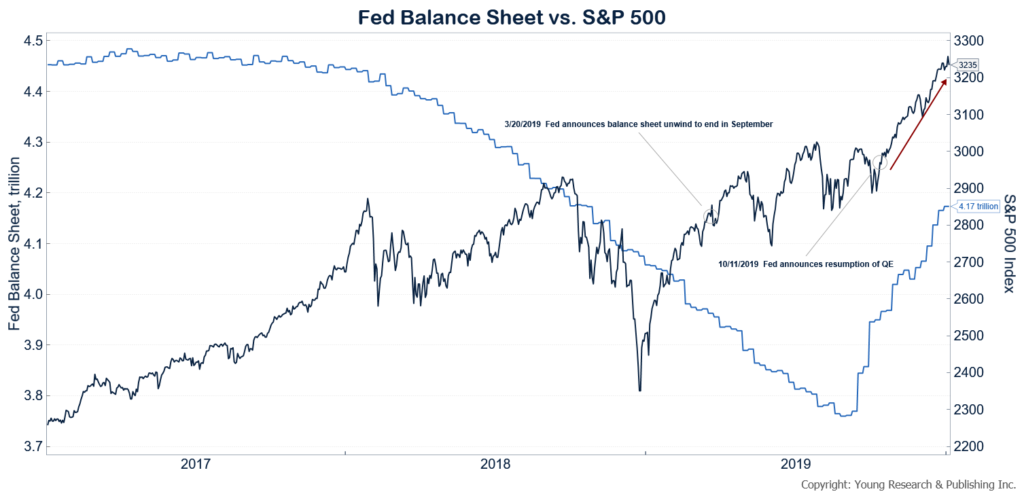

While swapping T-bills for bank reserves that pay interest, is not far from swapping five pennies for a nickel, the S&P 500 has responded about the same to the Fed’s non-QE as it did to past episodes of QE.

Over the course of three months, the Fed has undone more than half of the entire balance sheet unwinding that began in 2017. By the time non-QE, QE ends, the Fed’s balance sheet is likely to be back near a record.

What was once supposed to be an emergency measure to stem losses during the financial crisis has become standard operating procedure at the Fed.

Central bank intervention in markets has now been going on for so long that it seems normal, but there is nothing normal about regularly distorting markets on a massive scale.

The payback is likely to be ugly when it comes, the sharp correction in stocks in the 4th quarter of 2018 (the first time global central bank balance sheets shrank) foreshadows.

Trying to time such an event is never a useful exercise, but properly preparing your portfolio to weather a bust is indeed useful.