After hiking interest rates for the first time in over a decade last December, the Federal Reserve has sat on its hands all year. Four interest rate hikes were the Fed’s expectations in January, but a stock market correction scared off both the hawks and the doves. The Fed is now trying to signal that December is the next time it will hike rates, but it has cried wolf so many times, that markets no longer believe a hike is coming.

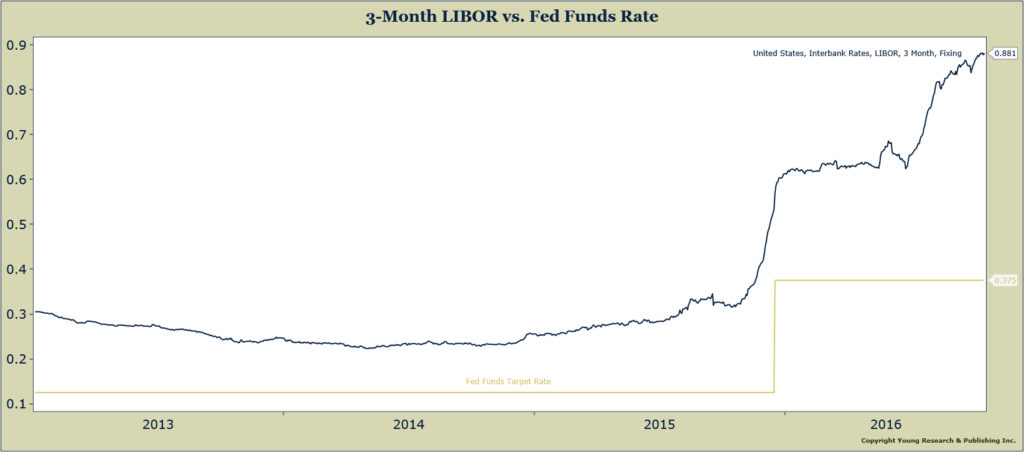

This timid approach to interest rate policy has robbed many investors of interest income, but one segment of the bond market has defied the will of the Fed has been floating-rate bonds. Floating rate bonds pay coupon payments that adjust with the level of short-term interest rates. The rate that many floating rate bonds are tied to is LIBOR, the London Interbank Offered Rate. New money market regulations that recently went into effect have helped push the LIBOR rate up even while T-bill rates remain depressed.

That’s been a windfall for investors in floating rate bonds. Okay, a relative windfall, but in an environment of negative and zero interest rates, every basis point counts.

Bloomberg has more of the details

The benchmark in question is not the Federal Reserve’s much-discussed overnight interest rate but rather three-month U.S. Libor, which has steadily risen ahead of new money-market rules going into effect on Friday. As much as $6.9 trillion of debt is pegged to this rate, including hundreds of billions of dollars of speculative-grade corporate loans.

Libor has risen to the highest level since 2009, even though the Fed’s benchmark has stayed constant. Given this discrepancy, it would be logical for companies to rely less on markets that are pegged to Libor and instead issue debt in fixed-rate markets that are more influenced by the fed funds rate.