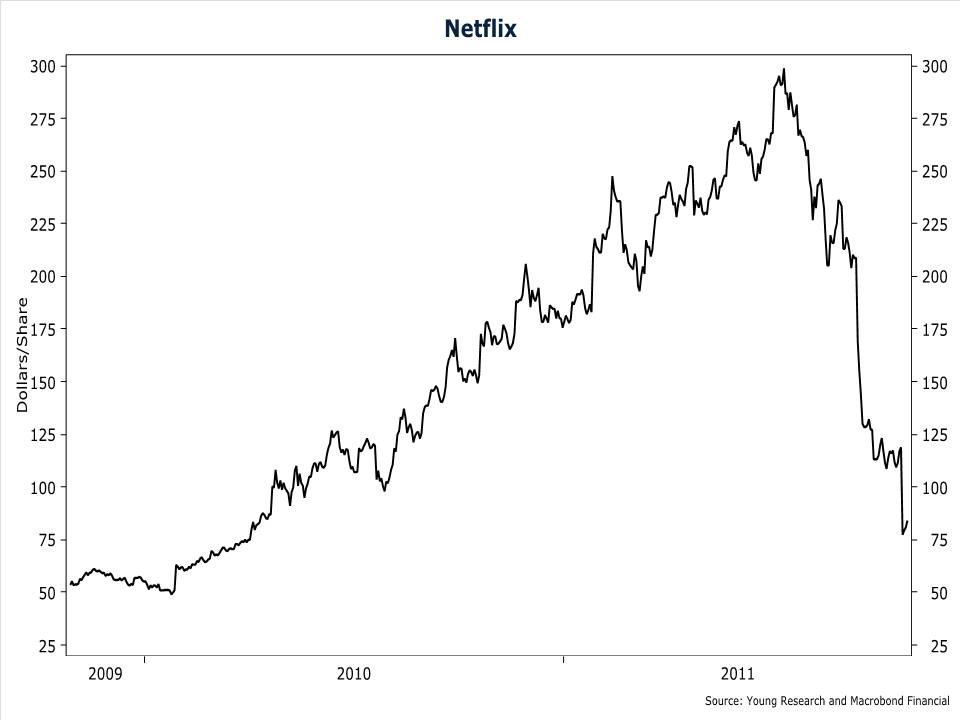

Most of you are no doubt familiar with Netflix—the leading DVD and video-streaming rental business in America. Up until recently, Netflix was a high flyer—a momentum stock. From year-end 2009 to June 2011, the shares rose over 375%—the highest return in the S&P 500. During the company’s 18-month price vault, revenue growth accelerated from 23% to 52%, and EPS growth averaged more than 57%. Those are impressive numbers for a company operating in the throes of a lackluster economy.

Investors were so impressed with Netflix’s business prospects that after paying 30X earnings in December of 2009, they bid the shares up to an outrageous 80X earnings earlier this year. Value investors were appalled. One hedge fund manager, Whitney Tilson, went so far as to short the stock, and publicly released his research. The shares traded near $180 when Tilson went public with his short case. Unconvinced by the analysis, investors continued to buy the stock. Tilson eventually covered his short at a higher price and with a big loss. The stock didn’t top out until it hit $298 per share.

But did Tilson have it wrong? Were Netflix prospects really so good that the company deserved an earnings multiple of 80X? Aren’t we talking about a company that just rents DVDs through the mail (a declining business) and streams digital data over the internet (a business with low barriers to entry)? Why would anybody pay such a lofty multiple for Netflix? Most Netflix bulls would likely cite the company’s growth prospects. But at an 80X multiple, the stock was already discounting a rosy growth scenario.

At the end of June, Netflix had about 24.5 million customers. There are about 131 million households in the U.S. Even if you assumed Netflix could fully penetrate all U.S. households over a 10-year period, you would only get growth of about 19% per year. Apply that growth rate to earnings and in 10 years Netflix would likely earn about $23 per share. Put a market multiple of 16 on the $23 per share in earnings and you get a 10-year price target of $368 per share. Assuming a $298 purchase price (the July high), the $368 price target would result in a 10-year average annualized return of about 2%. Clearly, those investors who bought Netflix near the 2011 high of $298 were anticipating much faster growth than the 19% in my simple example above.

As it turns out, a series of management missteps and an earnings miss caused Netflix investors who bought near the July high to reassess their optimistic growth forecast. The stock price tumbled more than 72% as a result and now trades at a much more realistic 19X earnings.

The takeaway here is to appreciate the role that expectations play in investing. Netflix is one of the fastest-growing big companies in America. But as some Netflix investors recently learned, identifying growth companies isn’t enough. If a stock’s price already reflects favorable prospects and those prospects fall short, the losses can be devastating.