Governor Jerome H. Powell testifies before a joint hearing of the Senate Banking Subcommittee on Securities, Insurance, and Investments and the Subcommittee on Economic Policy in Washington, D.C., on April 14, 2016.

The Federal Reserve delivered a sucker punch to retired investors yesterday.

The Fed managed to announce an even more dovish decision than Chairman Powell had hinted at in January. Powell took any additional rate increases off the table in 2019 and announced a much faster end to the roll-off of the Fed’s bloated balance sheet than expected.

Bonds will stop rolling off the balance sheet in September, with a reduction in the pace of roll-off starting in May. The Fed increased the size of its balance sheet by $3.6 Trillion during the crisis, but it is only taking back about $750 billion of that amount.

Sounds like debt monetization, does it not?

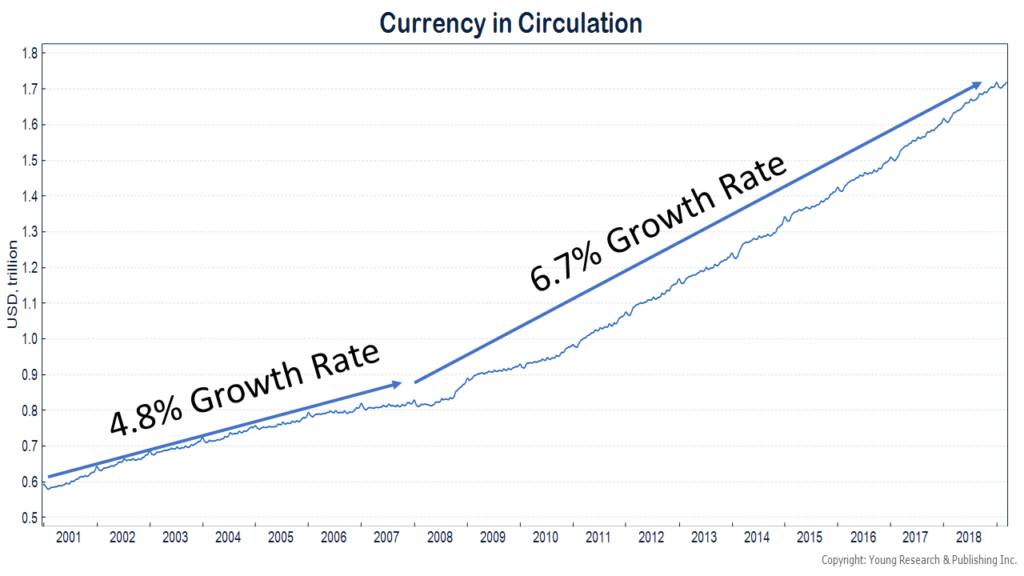

The Fed has a “yeah, but” for that. Yeah, but currency in circulation has soared and banks’ demand for reserves is high says the Fed.

Right!

We are supposed to believe that banks really prefer reserves (basically deposits that pay 2.4% interest) that much more than T-bills (highly liquid securities that pay 2.4%). The U.S. banking system has worked fine for at least a century on a low reserve regime. Would the Fed really be putting banks in a bind if it made them buy T-bills instead of reserves?

And though it may be true that currency has soared over the last decade, is anybody else at least a little bit curious as to why the acceleration started during the era of QE (see chart)?

The Fed justifies this pivot to an easy money stance by claiming that it hasn’t credibly achieved its symmetrical inflation target of 2%. In other words, Powell & Co., want to see inflation above 2% before they consider raising rates.

Core inflation is running at 1.94% today.

Apparently getting an indicator that measures inflation in a $21 trillion economy up a few basis points is really that important.

Hmmm!

The real motive here is obviously the level of asset prices. There’s really no other credible way to explain the Fed’s behavior. Managing the level of asset prices with monetary policy is a bankrupt strategy that is at the heart to the boom and bust cycles of the last two decades.

Ironically though, this dovish pivot appears to have backfired. After worrying for months that hiking rates would invert the yield curve, it was actually yesterday’s announcement that did the trick. The yield curve is inverted (short rates higher than long-rates) all the way out to 7 years.

An inverted curve is contractionary if it sustains. It will hurt the banks who boost the money supply that generates the inflation the Fed says it desires.

What’s that mean for you? Unfortunately another year of low interest rates.