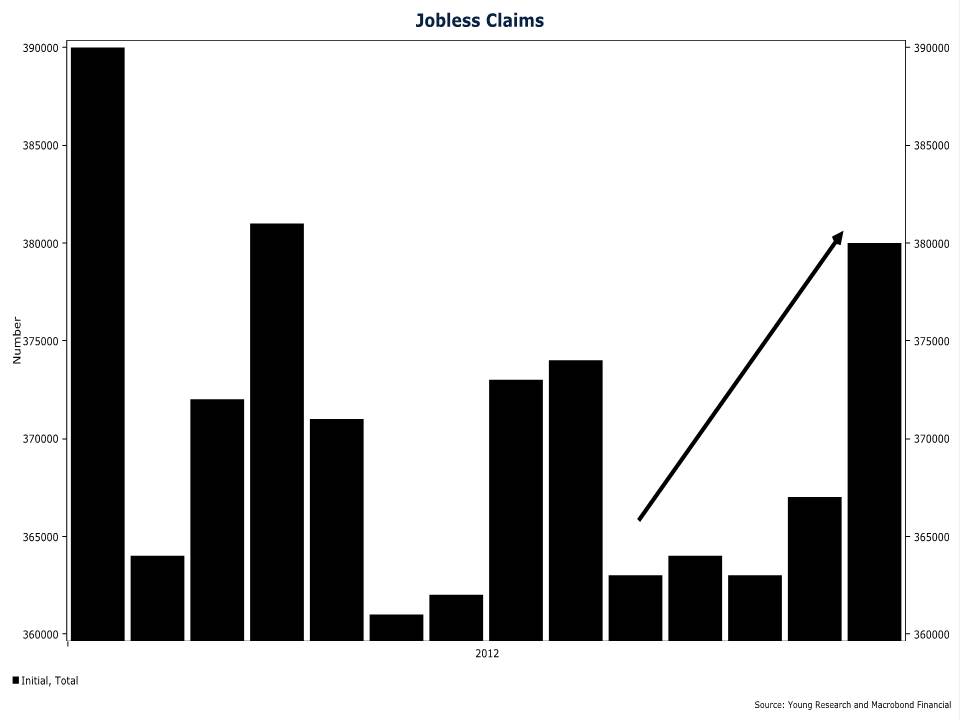

According to today’s report, initial claims for jobless benefits spiked to 380,000, the highest since January (See chart below). Compounding the fear about the recovery in jobs was the less than stellar growth logged in payrolls last week. Only 120,000 jobs were created in March, substantially underperforming average economists’ estimates which ranged closer to 200,000. Other economic data contradict the recent bad news. GDP is growing around trend, cars a selling fast and sentiment is trending upward. It’s safe to say that the economic data are mixed.

Also mixed is the interpretation of the data by Federal Reserve officials. The St. Louis Fed’s president, James Bullard has taken a cautious but optimistic view of the mixed data. He has been arguing against the Fed’s policy of waiting until 2014 to normalize rates, saying “The Committee’s practice of including distant dates in the statement sends an unwarranted pessimistic signal concerning the future of the U.S. economy.” Arguing against a third round of quantitative easing that may cause inflation, Bullard said “As the U.S. economy continues to rebound and repair, additional policy actions may create an over-commitment to ultra-easy monetary policy.”

Bullard’s hawkishness is not shared among the majority of Federal Reserve Open Market Committee members. Leading the dovish arm is the Fed Board of Governors Vice Chair, Janet Yellen. She said in a speech in New York yesterday “I consider a highly accommodative policy stance to be appropriate in present circumstances.”

The FOMC doves indicate through their statements that they believe the persistent high unemployment rate is caused by cyclical as opposed to structural factors. This is convenient for Fed policy makers because their academic models support the idea that monetary can help when unemployment is cyclical.

If unemployment is structural monetary policy is ineffective and in many cases counterproductive. Structural unemployment is caused by a mismatch between the skills of the unemployed workers and the skills demanded by employers. For example, if employers are hiring software engineers, but the majority of the unemployed are former carpenters and retail clerks, one might conclude unemployment is structural. Lowering interest rates isn’t going to allow a carpenter to take a job as a software engineer. In her speech Vice Chair Yellen said,

Some observers question just how large the shortfall from full employment really is and hence worry that further increases in aggregate demand could push up inflation. Their concern is that a large part of the rise in unemployment since 2007 is structural rather than cyclical. I agree that the magnitude of structural unemployment is uncertain, but I read the evidence as supporting the view that the bulk of the rise in unemployment that we saw in recent years was cyclical, not structural in nature.

Yellen doubles down on the notion that monetary policy can effectively fight today’s unemployment. She explains that today’s unemployment (which she believes to be cyclical) could lead to structural unemployment if left to fester. Her suggestion is that the Fed ought to keep pouring on the monetary stimulus until unemployment comes down. But that hasn’t worked yet, and there is no evidence it will.

While I do not see much evidence of any significant increase in structural unemployment so far, I am concerned that structural unemployment could increase over time if the labor market heals too slowly–a phenomenon known as hysteresis. An exceptionally large fraction of those now unemployed–more than 40 percent–have been out of work for six months or more. My concern is that individuals with such long unemployment spells could become less employable as their skills deteriorate and as they lose their connections to the labor market. This outcome does not appear to have occurred in the wake of previous U.S. recessions, but the fraction of the unemployed who have been out of work for a long period is much higher now than it has been in the past. To date, I have not seen evidence that hysteresis is occurring to any substantial degree. For example, the probability of finding a new job has not deteriorated more for individuals experiencing a long-term bout of unemployment relative to those facing shorter spells. Nonetheless, the risk that continued high unemployment could eventually lead to more-persistent structural problems underscores the case for maintaining a highly accommodative stance of monetary policy.

The mixed signals from economic data, and from the FOMC members themselves, argues for a wait and see approach. Pouring a third round of quantitative easing on an economy that is in mild recovery could spark an inflationary fire. Prudence is the best course for the Fed today.