Should you take investment advice from the mainstream internet (if I can coin a phrase)? Bloomberg posted an article on their website yesterday with the following headline:

“Goldman Sachs Sees More Value Outside of ‘Stretched’ U.S. Stocks”

Bearish views from Wall Street’s eternally bullish big banks are always of interest to me. Bearish views from Wall Street strategists are few and far between. Why? Being bearish on Wall Street is like opposing motherhood and apple pie. The big banks make more money when their clients are bullish. When investors are bearish fewer deals get done, fewer trades are booked, and clients tend to close. Plus, if a strategist’s bearish investment thesis isn’t proved right, he is often rewarded with a pink slip so there is a lot to lose for strategists who raise the flag of caution.

Why does Goldman think U.S. stock valuations are stretched?

According to the Bloomberg article, Goldman’s chief equity strategist David Kostin says “The only time during the past 40 years that the index [the S&P 500] traded at a higher multiple was during the 1997-2000 Tech Bubble.”

The tech bubble might have been the biggest stock market bubble in history, so if stocks are anywhere close to dotcom valuations we should all be able to agree that valuations must be stretched.

Bloomberg seems to acknowledge the stretched valuations, but then offers this scrap of misguided and misdirected advice.

Seven months after the Federal Reserve warned that valuations of some smaller, biotechnology and social-media stocks may be “stretched” in the U.S., Goldman Sachs Group Inc. is using the same word to describe the whole shebang.

“Stretched” valuations sound scary, but here’s something that may be even scarier: missing out on an 80 percent rally over the following three years because you got out of stocks when the market looked stretched. That would’ve been the case in 1997 when the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index first got to the valuation of 17.3 times estimated earnings for the next 12 months, which is also where it’s trading these days.

What’s happened since the Fed’s remarks about stretched valuations seven months ago? Well, the S&P 500 has gained almost 7 percent, the Nasdaq Composite Index is up 12 percent and the Russell 2000 Index of small caps is more than 5 percent higher. While the Solactive Social Media Index is down about 2 percent since then, the Nasdaq Biotechnology Index has surged more than 30 percent.

To sum up the Bloomberg analysis, stretched valuations don’t matter. But they do. The gaping hole in the Bloomberg analysis is that the author doesn’t mention what happens to stocks after the 80% rally from 1997-1999. Let me fill in the details for you.

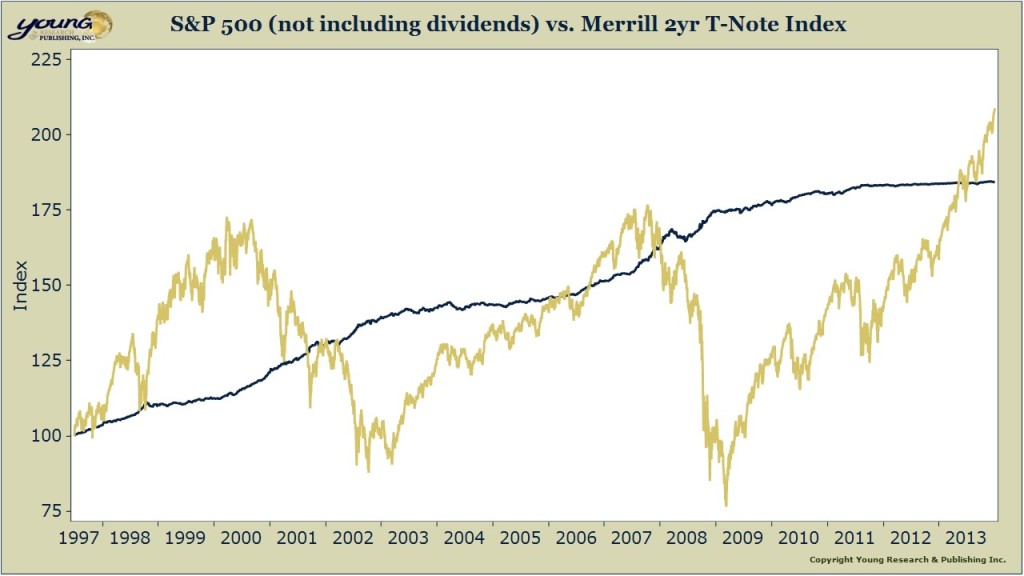

For our readers who didn’t live it, over the subsequent three years, stocks gave up every single point of that 80% return and then some. A $100 investment in the S&P 500 on June 30th of 1997 (when the index first crossed the 17.3X PE multiple referenced above), would have been worth $87 in October of 2002. About seven years after that in March of 2009 that $100 investment would have been worth $80. An investment in short-term Treasury notes made in June of 1997 would have performed better than the S&P 500 all the way up until May of 2013. That’s about 16 years. If you include dividends, short-term T-notes were the better investment until year-end 2011—still over 14 years.

What is the point here? There are three. Careful what you read on the mainstream internet. It could cost you serious money. Two, three years isn’t the long-term. It has always been true that a bubble can get bigger before it bursts. That doesn’t mean caution is not warranted. Trading the prospect of short-term pleasure for long-term pain has never been a good strategy. And three, valuations matter as always, but still over the long-run.