In a recent IMF working paper, author Shaun K. Roache provides readers with some valuable insight on China’s role in world commodity markets. It is no secret that China is a whale in the commodities space, but Mr. Roache helps readers understand just how much of an outlier China’s commodities consumption is when compared to the historical record. The title of the paper is China’s Impact on World Commodity Markets.

2.1. Long-term structural trends

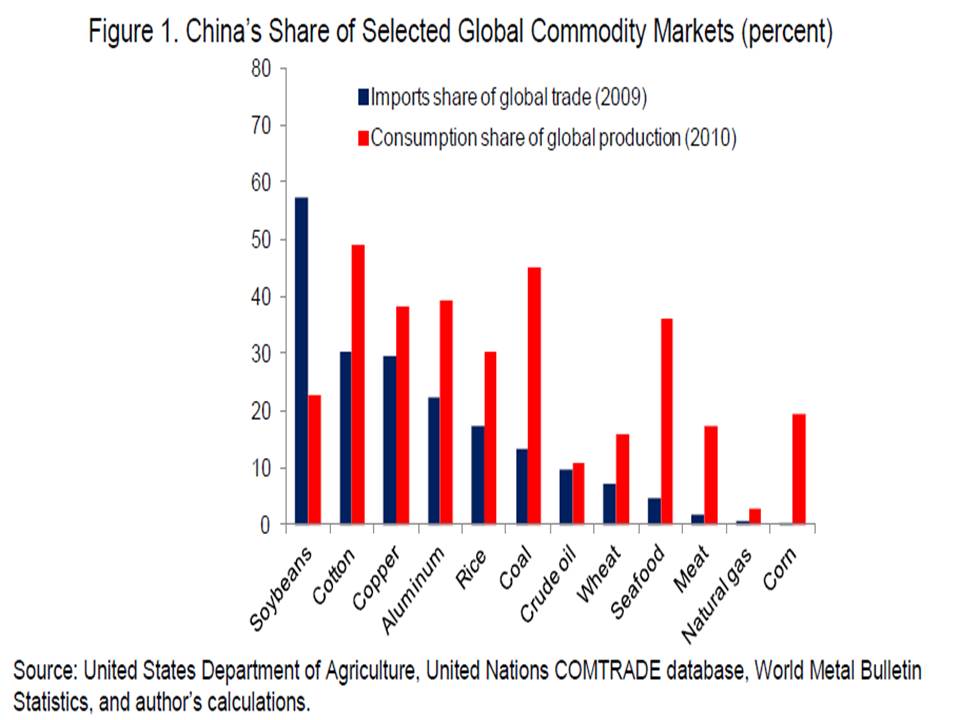

China is a large consumer of a broad range of primary commodities. As a percent of global production, China’s consumption during 2010 accounted for about 20 percent of non-renewable energy resources, 23 percent of major agricultural crops, and 40 percent of base metals. These market shares have increased sharply since 2000, mainly reflecting China’s rapid economic growth. History has shown that as countries become richer, their commodity consumption rises at an increasing rate before eventually stabilizing at much higher levels. This is often described as the S-curve.

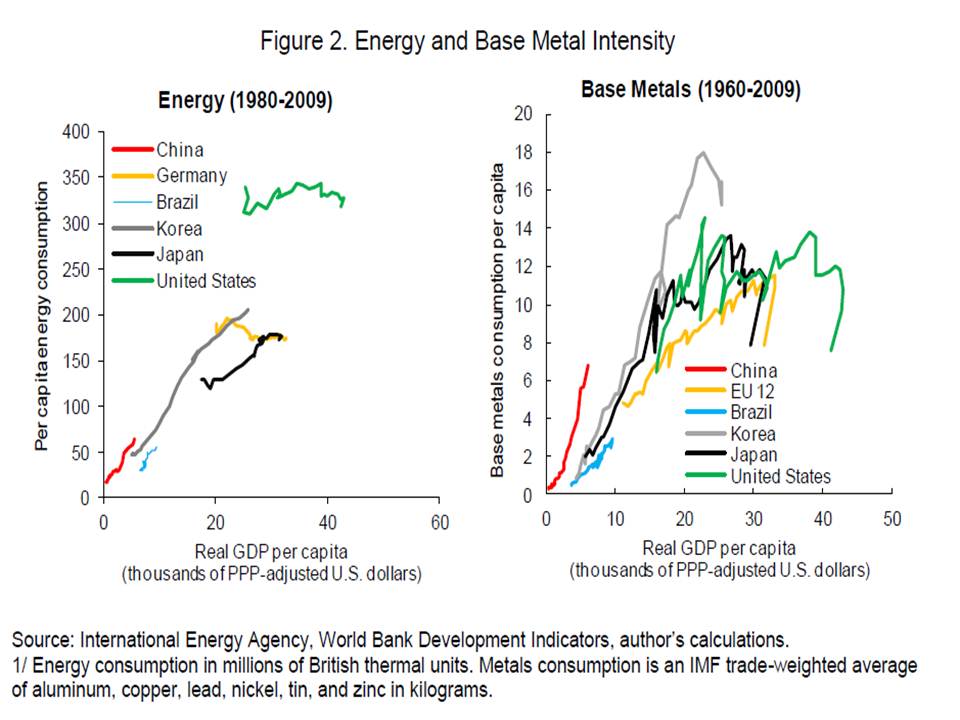

But this cannot explain all of the increase in China’s commodity consumption. China’s commodity intensity of demand has been growing particularly fast and is now unusually high. Intensity is sometimes measured by commodity consumption per capita and this is shown, alongside real GDP per capita, for China and five other G-20 economies since 1980 for energy and 1960 for metals in Figure 2. Moving along the line in a northeast/ east direction traces the evolution of commodity intensity forward through time, from the first year in the sample to 2009. Based on this small sample of countries, China’s energy consumption is shown to be relatively high given its stage of economic development. For example, China consumes about 35 percent more than Korea and twice the level of Brazil at comparable income levels. The difference is even larger for base metals, where China consumes significantly more than Korea and Brazil at the same income.

China’s unusually fast growing commodity intensity likely reflects the rapid expansion in the tradable export sector and large-scale fixed asset investment—particularly since 2000 (Yu, 2011). Both activities are commodity intensive. For example, Ye (2008) estimates that just over ½ of China’s copper usage is accounted for by infrastructure investment and construction, with ⅓ accounted for by consumer and industrial goods. It is beyond the scope of this paper to assess the root causes of China’s structure of economic growth and the high commodity intensity that results, but previous studies have highlighted the role of structural factors and domestic policy distortions (IMF, 2011a).