GMO’s second-quarter letter to investors, written by Ben Inker, is a master class on value investing and why value shares today look especially attractive relative to growth, aka glamour stocks.

Most will likely brush off GMO’s letter as the musings of a firm that has lost touch with a new paradigm in investing. “Today’s growth stocks are different than your father’s growth stocks,” the growth bulls will explain. “It’s all about innovation and disruption,” as if innovation and disruption are new phenomena.

Inker provides many insights on the Value vs. Growth debate, including why the last few months of value’s steep underperformance is nothing to worry about.

Argument five (explained below), gets to the heart of what many investors today will likely learn in time. Emphasis is ours. You can read the entire letter here.

Argument 5: Growth companies are simply better companies and make far more sense as long-term investments. You will never make 10 times your money in value stocks, whereas some growth stocks have risen well over 100-fold in the last 20 years. Growth stocks are destroying old companies and are changing the world.

Answer: It is almost invariably the case that the greatest buy and hold returns will come from successful growth companies.7 One dollar invested in Amazon on July 1, 2001 would have turned into almost $267 20 years later. But however obvious it may appear in retrospect that Amazon would become a colossus, picking winners is hard and the consequences of guessing wrong are generally severe. While it is not a fair analogy to equate buying Amazon stock 20 years ago to the purchase of a winning lottery ticket, what the two have in common is that an ex-post analysis of the results from those two outcomes is a lousy guide to the return to the general activity – purchasing highly priced growth stocks and purchasing lottery tickets.

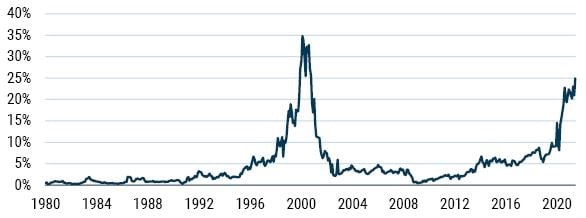

Our quarrel in any event is not with growth stocks per se, but the idea that you can buy stocks without regard to the price you are paying because the future fundamentals will be so wonderful that the price is irrelevant. When growth stocks are trading at a relatively modest premium to the market, we generally forecast that they will outperform, and we did so more or less continually in the U.S. from the fall of 2004 until the middle of 2015.8 When the premium gets significantly wider than historical averages, we start to get nervous, and when we see the premium get to extremes, we start to wonder if speculative mania has set in. Today looks to us like a mania. Exhibit 7 shows the percentage of the U.S. stock market trading at over 10x sales.

EXHIBIT 7: PERCENT OF U.S. STOCKS TRADING OVER 10X PRICE/SALES

Data from 1/1980-6/2021 | Source: GMO, Compustat

While there is no particular magic about 10x sales being the unique true sign of overvaluation, it has gained a certain amount of fame from a statement that Scott McNealy, co-founder and CEO of Sun Microsystems, made to Bloomberg in 2002:

…2 years ago we were selling at 10 times revenues when we were at $64. At 10 times revenues, to give you a 10-year payback, I have to pay you 100% of revenues for 10 straight years in dividends. That assumes I can get that by my shareholders. That assumes I have zero cost of goods sold, which is very hard for a computer company. That assumes zero expenses, which is really hard with 39,000 employees. That assumes I pay no taxes, which is very hard. And that assumes you pay no taxes on your dividends, which is kind of illegal. And that assumes with zero R&D for the next 10 years, I can maintain the current revenue run rate. Now, having done that, would any of you like to buy my stock at $64? Do you realize how ridiculous those basic assumptions are? You don’t need any transparency. You don’t need any footnotes. What were you thinking?9

It is not strictly impossible for a stock trading at 10x sales or more to give a good return. Amazon was trading at well over 10x sales in the fall of 1999, and the return from then has been a very healthy 18% annualized, or 38x total gain over 22 years.10 On the other hand, Amazon did fall by almost 93% from that peak to the low 2 years later, and an investor who had held off and only bought when its price/sales fell below 10 in late 2000 would have made 89x his initial investment and saved himself a good deal of initial pain.11

But the more important point is that the odds are strongly against companies trading at over 10x sales. Exhibit 8 shows the long-term real returns to a portfolio of stocks trading at 10x sales or more against the overall stock market.

EXHIBIT 8: PERFORMANCE OF STOCKS TRADING OVER 10X P/S VS. INDEXES

Data as of 6/30/2021 | Source: GMO, Compustat, Standard & Poor’s

The over 10x P/S portfolio is a market capitalization weighted portfolio of all stocks trading above 10x trailing 12-month sales, rebalanced monthly.The 10x sales cohort has underperformed the market by over 4% per year since 1980, reducing a 30x real gain over the 41 years in the S&P 500 to less than 4x, almost precisely in line with the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond index. While it is not impossible to prove worthy of such a high valuation, it takes extraordinary results to do so. And investing where it will take something extraordinary to earn a good return has generally been a bad idea despite the existence of a handful of exceptions to the rule.

Today, a full 25% of the U.S. stock market is trading above that 10x sales multiple, far higher than any time in history apart from the peak of the internet bubble in 2000. Will some of those companies prove worth their valuation in the long run? Almost certainly. But if history is any guide, the vast majority will not.